The COVID-19 crisis has pushed several plants to shut down. What should you consider as you prepare to take systems and equipment offline? What can small teams do to ensure future success of the plant? CBT partner Fluke Corporation, has a three-part plan for shutting your systems down, coming back online, and operating at-capacity systems. This is the first installment in the series, stay tuned for the next articles that will help you acclimate as business operations start to return to normal.

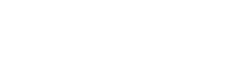

Most companies perform criticality analysis and risk assessment processes with varying degrees of success. A criticality analysis evaluates and classifies assets to provide clear understanding of which assets require immediate attention and which assets can wait. Too many managers make the mistake of taking an overly simplistic view of their criticality analysis and see only four options for maintaining their assets.

- Binary approach: divides a list of assets with a hard-cutoff line where everything above the line is critical and everything below is non-critical. The binary approach is self-defeating and improperly uses the criticality analysis to justify ignoring or under-maintaining many assets. Even assets below the cutoff line need some attention, and those assets—if neglected—can create problems that become critical. The so-called “non-critical” assets can have emergencies that force the maintenance team into a reactive maintenance mode.

- Dynamic approach: force-ranks every asset into a list where each asset is more critical than the one below it; start at the top of the list and get through as many assets as possible in a given period. Force-ranking often requires false precision and apples-to-oranges comparisons of dissimilar assets. It places too much emphasis on the mechanics of the scoring criteria and makes the scoring system work too hard. As people work on their way down the list, they can only maintain assets based on their available resources. While this approach offers the feel of flexibility, it ultimately ignores many assets and is unpredictable.

- Every asset on its own: a highly subjective variation of the dynamic approach; scheduling important assets for maintenance more frequently and less-important assets less frequently. This is the most common approach because to many, it feels like the best of all worlds. People can work their way down to the bottom of the criticality list (eventually) without increasing any resources. But good maintenance scheduling is a cornerstone of any top-performing maintenance program. People commonly fall into the trap of confusing scheduled maintenance with sufficient maintenance. They think simply having maintenance on a schedule is effective maintenance, and over time, they respond to time constraints by simply “thinning out” the schedule to push things out further—or they simply let tasks go overdue.

- Full coverage: concludes that most of the equipment is critical; scales up resources to have full coverage on all critical assets. They double the maintenance staff, send everyone to full cross-training and certification, and buy all new tools. Or worse, they may choose to keep their existing staff working perpetual overtime. This is the most expensive approach. In some cases, you are trading high immediate costs for long-term savings. Because of the high cost, this approach draws a lot of attention and scrutiny from upper management, heightening pressure to deliver immediate ROI. If any machines go down, it is often seen as proof that the maintenance program isn’t solving the problem. This breeds managerial impatience for immediate short-term returns. Finally, this approach implies that better maintenance is outside of our power. It suggests that improvement is determined entirely by circumstances and resources.

These four approaches are inflexible, unsustainable, and miss the root cause because they breed the wrong maintenance culture. A better approach is to divide your asset list into different classes, depending on how you plan to maintain each asset. There is more than one kind of critical.

A better way to classify your assets

A better way to manage this criticality dilemma is to get away from a simplistic “critical” or “non-critical” framework and re-classify your assets into more groups with very important distinctions. Take the preceding criticality scoring criteria and use it to answer one simple question:

What impact does this asset have on the company’s ability to generate revenue?

Critical assets can be divided into two groups: “star athletes” and “critical”

Star athletes

% loss of performance = direct loss of % of production or compliance. Needs constant assessment regardless of condition; must always run at peak performance.

% change in performance = % change in revenue

“Star athletes” refers to assets that directly determine the company’s ability to win, and by how much. Beyond simple uptime and downtime, there’s a direct relationship between each percentage of incremental performance and the incremental revenue of the company. Every bit of performance improvement means additional revenue. This is where maintenance must be at its peak. These assets need constant attention and monitoring, whether they are brand new or 30 years old.

Examples of star athlete assets include turbine generators, a large engine inside a ship, or a large process kiln or furnace. It’s not uncommon for a basic manufacturing plant to have no start athlete assets, and many companies have just one or two. But continuous process industries, such as oil and gas or chemical processing, often have multiple and interconnected star athlete assets—and maintenance teams, budgets, and tools to show for it.

Critical

Downtime/failure = loss of production or compliance. The result can be small or large, expensive or inexpensive, and still be critical.

Uptime = revenue; downtime = no revenue

“Critical assets” are those that must be up and running for the company to make money. Performance is less of an issue that whether the asset is on or off. If things are spinning, conveyors are moving, or hydraulics are actuating, the company can generate revenue. Uptime is the key performance indicator, and the ability to anticipate pending failures is highly valuable.

“Star athletes” and “critical assets” don’t have to be big, expensive, complex, or heavy duty. Sometimes a chemical process can depend on a simple solenoid valve, or a food processing line can depend on whether a $20 motor is dispensing material out of a hopper. Criticality is not about an asset’s complexity, but about the effect it has on the ability to generate revenue.

Non-critical assets can be divided into two groups: “semi-critical” and “non-critical”

Semi-critical

Downtime/failure = strain on production or compliance. This is highly dependent on lead time. If strain on production leads to loss of production, assets that can be easily repaired or replaced within that timeframe are classified as semi-critical (assets that might not be repaired or replaced during that timeframe are critical).

Downtime = strain on production or compliance

“Semi-critical assets” are those that, when they go down, don’t necessarily stop production—but they do put strain on the system. Think of a warehouse or distribution center that has four forklifts. If one goes down, things keep moving, but the remaining forklifts must work 33% faster or longer. Or think of a rivet press that goes down, resulting in production personnel having to manually drive the rivets to keep up the production volume.

In some cases, a company or a process can only tolerate the loss of a semi-critical asset temporarily before it becomes unsustainable or the process falls too far out of balance.

Non-critical

There may be reasons to fix these assets, but not because of direct production loss or compliance—those are not affected by non-critical assets.

Downtime = no immediate effect on production

“Non-critical assets” do not affect the company’s ability to generate revenue—no matter how big, expensive, or complex they may be. For example, consider a rotating company sign in from of a building.

What about municipal services, public facilities, non-profit organizations, or other entities that don’t generate revenue? For those cases, replace the idea of generating revenue with fulfilling the organization’s mission, operating within budget, or providing the expected level of service.

It’s important to remember that criticality classification is unique to each company. What may be a non-critical luxury at one company may well be a star athlete at another. There are multiple tools that can help you keep your plant up and running.

Additional Resources:

When and how to use and set up vibration monitoring on assets

4 ways maintenance teams benefit from remote power monitoring

![]()